What is Dana?

Dana is a word in the Pali language meaning giving, offering, generosity or liberality, and refers to the act of intentionally giving something to another person. Generosity, or “caga”, in actuality is one’s internal disposition or a quality of mind that leads to acts of giving. However, in discussing the virtue of giving in Buddhist literature, giving and generosity are often discussed interchangeably. The quality of generosity predisposes one to give (dana) and the act of giving can facilitate the development of the quality of generosity (caga). Because giving and generosity are interdependent and intertwined in such a way, the two terms will hereafter be used interchangeably. (“Dana: Giving in Theravada Buddhism” by Dr. Ari Ubeysekara)

Liberality, especially the offering of robes, food, etc. to the monks, is highly praised in all Buddhist countries of Southern Asia as a fundamental virtue and as a mean to suppress man’s inborn greed and egoism. But, as in any other good or bad action, so also in offering gifts, it is the noble intention and volition that really counts as the action, not the mere outward deed. Almsgiving or liberality constitutes the first kind of the ten meritorious activity, the other two being morality and mental development. (“Buddhist Dictionary”, Nyanatiloka)

Generosity (caga) is glad willingness to share what one has with others. In Buddhism, generosity is seen as a strategy to weaken greed, a way of helping others and a means of lessening the economic disparities in society. Since it is one of the cardinal Buddhist virtues, the Buddha has a great deal to say about giving and sharing.

The Function of Giving

Giving is of paramount importance to the Buddhist for mental purification because as it is the foremost weapon against greed, the first of the three unwholesome motivational roots. Greed wraps egoism and selfishness since we grasp on to our personalities and our possessions as “I” and “mine”. Giving helps make egoism thaw and is the antidote to cure the illness of egoism and greed.

“Overcome the taint of greed and practise giving. Therefore, having removed stinginess, the conqueror of the stain should give a gift, deeds of merit are the support for living beings when they arise in the other world,” prompts the Devatasamyutta [“Stinginess” (S.l, 32)]. The Dhammapada echoes an act of giving has been compared “to fighting a war as various enemies such as greed, attachment and other mental defilements will fight very hard to defeat and sabotage it and to conquer miserliness with generosity”. (Dhp. 223)

It is difficult to exercise the virtue of giving proportionate to the intensity of one’s greed and selfishness: “Some provide from the little they have, others who are affluent don’t like to give. An offering given from what little one has is worth a thousand times the value.” It also equates giving to a battle where one has to fight the evil forces of greed before one can make up one’s mind to give away something dear and useful to oneself. “Giving and warfare are similar, they say: A few good ones conquer many if one with faith gives even a little. He thereby becomes happy in the other world.” [Devatasamyutta “Good” (S.l, 33)]

The Latukikopama Sutta MN 66 elucidates how a man, named Udayin, lacking in spiritual strength finds it hard to give up an evening meal he has been used to: “Venerable sir, I was upset and sad, thinking, ‘The Blessed One tells us to abandon the most sumptuous of our two meals. The Sublime One tells us to relinquish it.’ ” The Sutta, then, gives an analogy how a small quail can come to death when it gets entangled even in a useless rotten creeper. “Though weak, a rotten creeper is a great bond for the small bird. But even an iron chain may not be too big a bond for a strong elephant.” (M.i, 449) Similarly, a poor wretched man of weak character would find it difficult to part with his shabby meagre belongings, while a strong-character king will even give up a kingdom once convinced of the dangers of greed.

Miserliness is not the only hindrance to giving. Carelessness and ignorance of the working of kamma and survival after death are equally valid causes. If one knows the moral advantages of giving, he will be vigilant to seize opportunities to practice this great virtue. “Through stinginess and negligence a gift is not given. One who knows, desiring merit should surely give a gift.” (S.l, 32)

Once the Buddha said “If beings, knew, as I know, the result of giving and sharing, they would not eat without having given, nor would they allow the stain of meanness to obsess them and take root in their minds. Even if it were their last morsel, their last mouthful, they would not eat without having shared it, if there were someone to share it with.” [“26 The Alms Sutta” (It.I.3.6), P. Masefield; “Giving Dana Sutta” (It.22-13), John D. Ireland); (It.19)]

“There are these five timely gifts: (1) One who gives a gift to a visitor; (2) to one who is setting out on a journey, (3) to a patient, (4) gives during a famine, (5) one first presents the newly harvested corps and fruits to the virtuous ones.” [“Timely Gift” (A.V, 36)]

“When the three things are present, a clansman endowed with faith generates much merit. What three? (1) When faith is present, a clansman endow with faith generate much faith. (2) When an object to be given is present, a clansman endowed with faith generates much faith. (3) When those worthy of offerings are present, a clansman with faith generates much faith.” [“Present”, (A. III, 41)]

The Value Of Giving

Many suttas enumerate the various benefits of giving. Giving promotes social cohesion and solidarity. It is the best means of bridging the psychological gap, much more than the material economic gap, that exists between haves and have-nots. “Make your offering with your mind completely calm and contented and fill the offering-mind with the giving you can be free from ill-will.” [“Magha Sutta, III.5” (Sn. 506)] The one with a generous heart earns the love of others and many associate with him. “By giving he becomes dear, and many resort to him, he attains a good reputation and fame, he is composed and confidently enters the assembly.” [“Siha” (A.V, 34(4))] Giving also cements friendships. “Doing what is proper, dutiful with initiative, finds wealth by truthfulness, wins acclaims by giving, one binds friends.” [“Alavaka Sutta 1/7”, (Sn. 187)]

“He who gives alms, bestows a fourfold blessing: he helps to long life, good appearance, happiness and strength. Therefore long life, good appearance, happiness and strengthen will be his share, whether amongst heavenly beings or amongst human” [“Suppavasa” (A. IV, 57); “Sudatta” (A. IV, 58)]

There are also further five blessings accrue to the giver of alms: (1) One is dear and agreeable to many people. (2) Good persons resort to one. (3) One acquires a good reputation. (4) One is not deficient in lay person’s duties. (5) With the breaking up of the body, after death, one is reborn in good destination, in a heavenly world.” [“The Benefits of Giving”, (A.V, 35)]

It is maintained that if a person makes an aspiration to be born in a particular place after giving alms, the aspiration will be fulfilled only if he is virtuous, but not otherwise. “Bhikkhus, there are these eight kinds of rebirth in account of giving. Here someone gives a gift to an ascetic or a brahmin, food and drink, clothing and vehicles, garlands, scents and unguents, bedding, dwellings, and lighting. Whatever he gives expects something in return…

“If he sees affluent khattiyas, affluent Brahmins, or affluent householders enjoying themselves with the five objects of sensual pleasures and made a wish after death to be reborn in their companionship and develops his mind on it. That aspiration resolves on what is inferior and leads to rebirth there for one who is virtue and not immoral succeeds because of his purity.

“If he has heard that devas who ruled by the four kings, the Tavatimsa devas, Yama devas, Tusita devas, the devas who delight in creation and the devas who control what is created by other and the devas of Brahma’s company, who are long-lived and beautiful and abound in happiness and occurs to him to make that aspiration after death to be reborn in their companionship.” [“Rebirths on Account of Giving”, (A.VIII, 35(5))]

According to one sutta, if one practises giving and morality to a very limited degree and has no idea about meditation, one obtains an unfortunate birth in the human world. “Someone has practised the basis of merit activities of giving consisting in giving to a limited extent; he has practised the basis meritorious activity consisting of in virtuous behaviour to a limited extent, but has not taken the basis of meritorious activity consisting in meditative development, after death is reborn among humans in an unfavourable condition.”

If one who performs meritorious deeds such as giving and morality to a considerable degree, but does not understand anything about meditation, meets a fortunate human birth. “Someone who has practised the basis of meritorious activity consisting in giving to a middling extent, but he has not undertaken the basis of meritorious activity consisting in meditative development, upon death he is reborn among humans in a favourable condition.”

But those who practise giving and morality to a great extent without any knowledge of meditation find rebirth in one of the heavens. They excel other deities in the length of life, beauty, pleasure, fame and the five strands of sense pleasure. “Someone who has practised the basis of meritorious activity consisting in giving to a superior extent; he practised the basis of meritorious activity consisting in virtuous behaviour to superior extent, but he does not undertaken the basis of meritorious activity consisting in meditative development, upon death he is reborn in the companion of devas.” [“Activity” (A.IV, 36(6))]

“Alms given to recluses and brahmans who follow the Noble Eightfold Path yield wonderful results just as seeds sown on fertile, well-prepared, well-watered fields produce abundant crops.” [“The Field” A.Vlll, 34(4)]

Having given such alms given without any expectations whatsoever can lead to birth in the Brahma-world at the end of which one may become a non-returner. “Having given such gift upon death will be reborn in the companionship with the devas of Brahma’s company. Having exhausted that kamma, psychic potency, glory, and authority, he does not come and return to this state of being.” [“Giving” (A.VII, 52(9))]

The Dakkhinavibhanga Sutta (M 142) enumerates a list of persons to whom alms can be offered and the merit accruing therefrom in ascending order. “There are fourteen kinds of personal offerings.

One gives a gift to the Tathagate, this is the first kind of personal offering, a paccekabuddha is the second, to an arahant disciple of the Tathagate, this is the third, to the one who has entered the way to the realisation of the fruit of arahantship is the fourth, to a non-returner this is the fifth, to one who has entered upon the way to the realisation of the fruit of non-returner the sixth, to a once-returner is the seventh, to one who has entered upon the way to the realisation of the fruit of once-returner is the eight, to a stream-enterer is the ninth, to one who has entered upon the way to realisation of the fruit of stream-entry is the tenth, to one outside (the Dispensation) who is free from lust from sensual pleasure, this the eleventh, to a virtuous ordinary person, this is the twelfth, to an immoral person ordinary person this is the thirteenth and to an animal is the fourteenth kind of personal offering.

“A thing given to an animal brings a reward a hundredfold. A gift given to an ordinary person of poor moral habit yields a reward a thousand fold; a gift given to a virtuous person yields a reward a hundred thousand fold. When a gift is given to a person outside the dispensation of Buddhism who is without attachment to sense pleasures, the yield is a hundred thousand-fold of crores. When a gift is given to one on the path to stream-entry the yield is incalculable and immeasurable. So what can be said of a gift given to a stream-enterer, a once-returner, a non-returner, an arahant, a paccekabuddha, and a Fully Enlightened Buddha?” (M. iii, 254-55)

The same sutta emphasizes that a gift given to the Sangha as a group is more valuable than a gift offered to a single monk in his individual capacity, even to monks who immoral and evil character in the name of the Sangha order. It is said that “in future times, there will be members of the clan who are ‘yellow-necks’, immoral of evil character and people will give gifts to those immoral persons for the sake of the Sangha. Even then an offering made to the Sangha is incalculable, immeasurable. And I say that no way is a gift to a person individually ever more fruitful than to an offering to the Sangha.” (M. iii, 256) But it should be observed that this statement is contradictory to ideas expressed elsewhere, that what is given to the virtuous is greatly beneficial but not what is given to the immoral.

(The commentary states that a gift offered to an immoral bhikkhu taken to represent the entire Sangha is more fruitful than a gift offered to a personal basis to an arahant. But for the gift to be properly presented to the Sangha, the donor must take no account of the personal qualities of the recipient but must see him solely as representing the Sangha as a whole).

The Buddha once explained that it is a meritorious act even to throw away the water after washing one’s plate with the generous thought that may the particles of food in the washing water be food to the creatures on the ground. When that is so, how much more meritorious it is to feed a human being and is more meritorious to feed a virtuous person. “That one acquires merit even if one throws away dishwashing water in the refuse dump or cesspit with the thought: ‘May the living beings here sustain themselves with this!’ How much more, then, (does one acquire merit) when one gives to human beings! What is given to one of virtuous behaviour is more fruitful than to an immoral person. And the most worthy recipient is one who has abandoned five factors and possesses five factors.” [“Vacha” (A.III, 57(7))]

Another sutta maintains that it is not possible to estimate the amount of merit that accrues when an offering is endowed with six particular characteristics. Three of the characteristics belong to the donor while three belong to the donee. “What are the three characteristics of a donor? (1) The donor is joyful before giving; (2) has a placid, confident mind in the act of giving, and (3) is elected after giving. These are the three characteristics of a donor. What are the characteristics of a recipient? Here, (4) the recipients are devoid of lust or are practising to remove lust; (5) they are devoid of hatred or are practising to remove hatred; (6) they are devoid of delusion or are practising to remove delusion.”

When an almsgiving is endowed with these qualities of the donor and donee, the merit is said to be as immeasurable as the waters in the ocean: “Just so much is the stream of merit, stream of the wholesome, nutriment of happiness, that leads to what is wished for, desirable and agreeable, to one’s welfare and happiness is reckoned simply as an incalculable, immeasurable, great mass of merit, just as it is not easy to measure the water in the great ocean.” [“Giving” (A.VI, 37(7))]

The Ghatikara Sutta MN 81, records a unique almsgiving where even the donor, Ghatikara the potter and chief benefactor of Buddha Kassapa was not present. He was a non-returner who did not want to enter the Order as he was looking after his blind, aged parents. One day the Buddha Kassapa went to his house on his alms round, but Ghatikara was absent, and the blind parents invited the Buddha to serve himself from the pots and pans and partake of a meal. When Ghatikara returned and inquired, “Who has taken rice from the cauldron and sauce from the saucepan, eaten and gone away?” and on another occasion “Who has taken porridge from the vessel and sauce from the saucepan, eaten and gone away?” The parents informed him, “My dear, the Blessed One Kassapa, accomplished and fully enlightened did.” It is said that the joy and happiness he experienced did not leave him for two weeks, and the parents’ joy and happiness did not wane for a whole week. (M.ii, 53)

The same sutta reports that on another occasion the roof of the Buddha Kassapa’s monastery started leaking. He sent the monks to Ghatikara’s house to fetch some straw, but Ghatikara was out at the time. Monks came back and said that there was no straw available there except what was on the roof. The Buddha asked the monks to get the straw from the roof there. Monks started stripping the straw from the roof and the aged parents of Ghatikara asked who was removing the straw. The monks explained the matter and the parents said, “Please do take all the straw.” When Ghatikara heard about this he was deeply moved by the trust the Buddha reposed in him. The joy and happiness that arose in him did not leave him for a full fortnight and that of his parents did not subside for a week. For three months Ghatikara’s house remained without a roof with only the sky above, but it is said that the rain did not wet the house. Such was the great piety and generosity of Ghatikara. (M.ii, 54)

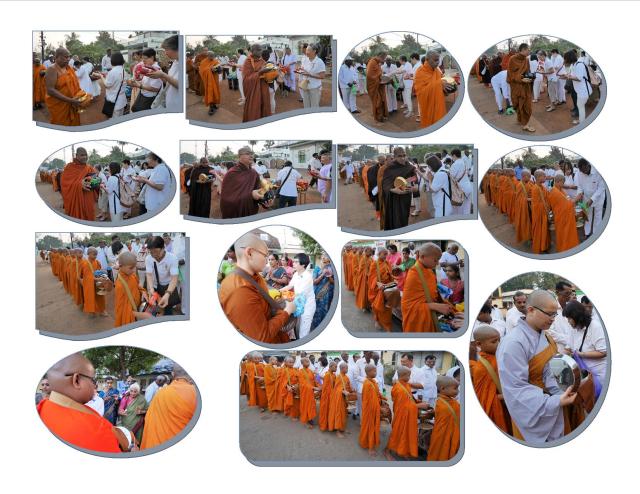

The Manner to Give Dana

Practice of cultivating generosity is an integral aspect of Buddhist practice. Giving with an open and generous heart allows the giver to practise renunciation and letting go of his/her attachment towards possessions, which facilitates the letting go of various ways the mind holds onto self-view.

Dana, giving, is extolled in the Pali canon as a great virtue. It is, in fact, the beginning of the path to liberation. When the Buddha preaches to a newcomer he starts his graduated sermon with an exposition on the virtues of giving. Of the three bases for the performance of meritorious deeds, giving is the first, the other two being virtue and mental cultivation.

The attitude of the donor in the act of giving makes a world of difference for the goodwill between the donor and recipient irrespective of whether the gift given is big or small:

“Alms should be given in such a way that the donee does not feel humiliated, belittled or hurt. The needy ask for something with a sense of embarrassment, and it is the duty of the donor not to make him feel more embarrassed and make his already heavy burden still heavier.

Alms should be given with due consideration and respect. The recipient should be made to feel welcome. It is when a gift is given with such warmth that a cohesive mutually enriching friendliness emerges between the donor and donee.

One should give with one’s own hand. The personal involvement in the act of giving is greatly beneficial. This promotes rapport between the donor and donee and that is the social value of giving. Society is welded in unity with care and concern for one another when generosity is exercised with a warm sense of personal involvement.

One should not give as alms what is only fit to be thrown away. One should be careful to give only what is useful and appropriate. One should not give in such a callous manner so as to make the donee not feel like coming again.

Giving with faith especially when offering alms to the clergy one should do so with due deference and respect, taking delight in the opportunity one has got to serve them.

Once should also give at the proper time to meet a dire need. Such timely gifts are most valuable as they relieve the anxiety and stress of the supplicant.

One should give with altruistic concerns, with the sole intention of helping another in difficulty. In the act of giving one should take care not to hurt oneself or another.

Giving with understanding and discretion is praised by the Buddha. If a gift contributes to the well-being of the donee it is wise to give. But if the gift is detrimental to the welfare of the donee one should be careful to exercise one’s discretion.” [“A Bad Person” (A.V, 147(2)); “A Good Person” (A.V, 148(8))]

Giving as described above is highly commended as noble giving. More than what is given, it is the manner of giving that makes a gift valuable. One may not be able to afford a lavish gift, but one can always make the recipient feel cared for by the manner of giving.

“He gives what is pure, excellent, timely, allowable, after investigation, gives often, while giving he settles his mind in confidence and having given he is elated.” [“The Good Person’s Gift” (A.VIII, 37)]

“There are these eight types of gifts givers. (1) Having insulted (the recipient) one gives a gift. (2) One gives a gift from fear. (3) One gives a gift (thinking) ‘He gives me.’ (4) One gives a gift (thinking) ‘He will give to me.’ (5) He gives a gift, (thinking) ‘Giving is good.’ (6) He gives a gift (thinking) ‘I cook, these people do not cook. It isn’t right that I that I who cook should not give those who do not cook.’ (7) One gives a fit (thinking) ‘Because I have given this gift, I will gain a good reputation.” (8) One who gives a gift for the purpose of ornamenting and equipping the mind.” [“Giving”, (A.VIII, 32.1)] “By relying on a good person, four benefits are to be expected. What four? One grows in noble virtuous behaviour, in noble concentration, in noble wisdom and in noble liberation.” [“Benefits of a Good Person” (A.IV, 242)]

The Qualities Of Donor

In “The Rainless One Sutta 75” the Buddha metaphorically compared the three types of donors: “the one who is the same as a rainless one, as a local rain one and the one who pours down everywhere. In the case of a rainless one who becomes a non-giver of food, drink, clothing, vehicles, garlands, scents or cosmetics, bed or lodging, or a lamp and things to light it with, to anyone at all, be they recluses, brahims, street people, charlatans or beggars. A local rain donor is an individual who fails to give to some and confers to some, and the one who pours down everywhere is an individual who give in abundance, just as a storm cloud thunders, rumbles, and then begins to rain, filling (everywhere) with water, completely submerging high ground and hollow.” [“A Rainless Cloud” (It.III.3.6), P. Masefield; “Avutthika Sutta” (It. 26-13), John D. Ireland; It.65]

“A good person gives a gift out of faith, gives respectfully, in a timely manner, unreservedly and without injuring himself or others. The results of the gift: he becomes rich with great wealth and property, is handsome, attractive, graceful, possessing supreme beauty and complexion.” [“A Good Person”, (A.V, 148)] “Faith, moral shame, and wholesome giving are qualities pursued by a good person; for thus they say, is the divine path by which one goes to the world of the devas.” [Giving” (A.VIII, 32.2)]

A noble giver is one who is happy before, during and after giving. “Before giving he is happy anticipating the opportunity to exercise his generosity. While giving he is happy that he is making another happy by fulfilling a need. After giving he is satisfied that he has done a good deed.” [“Giving“ (A.VI, 37)]

Generosity as one of the important qualities that go to make a gentleman, “Bhikkhus, you should remember Hatthaka of Alavi as one who possesses eight astounding and amazing qualities: (1) He is endowed with faith; (2) is virtuous; (3) has a sense of moral shame and (4) moral dread. (5) He is learned, (6) generous, and (7) wise. (8) He has few desires.” [“Hatthaka”, (A. VIII, 24)]

The Buddha compares the man who righteously earns his wealth and gives of it to the needy to a man who has both eyes, whereas the one who only earns wealth but does no merit is like a one-eyed man. ”One with two eyes is said to be the best kind of person whose wealth is acquired with his own exertion with goods right righteously gained.” while “The person described as one-eyed is a hypocrite who seeks wealth (sometimes) righteously and (sometimes) unrighteously.” [“Blind”, (A.III, 29)]

The wealthy man who enjoys his riches by himself without sharing is said to be digging his own grave. “Having ample wealth, assets and property, enjoying them alone – this is a cause of one’s downfall.” [“Parabhava Sutta”, (Sn. 102)]

“A bad person gives a gift causally, without reverence, not by his own hands, gives what would be discarded and without a view about the returns of giving. A good person respectfully, with reverence, with his own hands, gives what would not be discarded and with a view about the returns of giving.” [“A Bad Person”, (AN.V, 147)]

“There are these four purifications of offerings: (1) an offering that is purified through (1) the donor but not through the recipients whereby the donor is virtuous and of good character but the recipients are immoral and of bad character; (2) through the recipients but not the donor whereby the donor is immoral and of bad character but the recipients are virtuous and of good character; (3) through neither donor nor recipients where both the them are immoral and of bad character; (4) through both donor and recipients where both of them are virtuous and of good character.” [”Offerings” (A.IV, 78); (M.iii, 257)] The donor is also described as a person who keeps an open house for the needy. He is also like a well spring for recluses, brahmins, the destitute, wayfarers, wanderers and beggars. Being such a person does meritorious deeds is munificent and is interested in sharing his blessings with others. He is a philanthropist who understands the difficulties of the poor. He is open-handed and is ready to comply with another’s request. He is one fit to be asked from and takes delight in distributing gifts to the needy, and has a heart bent on giving. Such are the epithets used in the suttas to describe the qualities of the liberal-minded donors.

The Donations

Practically anything useful can be given as a gift. The Niddesa, the eleventh book of the Khuddaka Nikaya, (ND.2, 523) gives a list of fourteen items that are fit to be given for charity. They are robes, alms food, dwelling places, medicine and other requisites for the sick, food, drink, cloths, vehicles, garlands, perfume, unguent, beds, houses and lamps. (Source: The Buddhists Encyclopaedia of Buddhism, Editor Subodh Kapoor, 2001)

It is not necessary to have much to practise generosity, for one can give according to one’s means.

Gifts given from one’s meagre resources are considered very valuable: “Some provide from the little they have while others who are affluent don’t give. An offering given from what little has is worth a thousand times it value.” [“Stinginess Sutta”, (S.I, 32)] and one “should give when asked even if it is only a little, one may go to the world of the deva.” (Dhp. 224)

If a person leads a righteous life even though he ekes out a bare existence on gleanings, looks after his family according to his means, but makes it a point to give from his limited stores, his generosity is worth more than a thousand sacrifices. “If one practises the Dhamma, though getting on by gleaning, while supporting his wife gives from the little he has, then a hundred thousand offerings of those who sacrifice a thousand are not worth even a fraction.” [“Stinginess” (S.l, 32)]

Alms given from wealth righteously earned is greatly praised by the Buddha, “This indeed is the suffering of bondage from which the wise person is freed, giving (gifts) with wealth righteously gained, settling his mind in confidence.” [“Debt”, (A. VI, 45); “Utilisation”, (A.V, 41)]

In the Magha Sutta, the Buddha highly appreciates a householder Magha who earns through righteous means and liberally give of it to the needy: “Young man, all these gifts and offerings you make are certainly worthwhile and they do produce great merit. It is the same for any man who makes donations and given support, and stay s approachable and open to requests, and who shares his lawful profits amongst one or to or twenty or thirty, or a hundred people, or more. All these gifts will bring great merit to him.” (Sn.III, 5)

Even if one gives a small amount with a heart full of faith one can gain happiness hereafter. According to the “Acamadayikavimana, (Rice-Crust Giver’s Mansion)” the alms given consisted of a little rice crust, but as it was given with great devotion to an eminent arahant, the reward was rebirth in a magnificent celestial mansion. [(Vim.III, 3(20)]

The Dakkhainavibhanga Sutta (M 142) states that “an offering is purified on account of the giver when the giver is virtuous, on account of the recipient when the recipient is virtuous, on account of both the giver and the recipient if both are virtuous, by none if both happen to be impious.” [(M.iii, 257); ”Offerings” (A.IV, 78)]

There are these five great gifts which have been held in high esteem by noble-minded men from ancient times. Their value was not doubted in ancient times, it is not doubted at present, nor will it be doubted in the future. The wise recluses and brahmans had the highest respect for them. These great givings comprise the meticulous observance of the Five Precepts. By doing so one gives fearlessness, love and benevolence to all beings. If one human being can give security and freedom from fear to others by his behaviour, that is the highest form of dana one can give, not only to mankind, but to all living beings. “There are, bhikkhus, these five gifts, great gifts, primal, of long standing, traditional, ancient, unadulterated and never before adulterated, which are not being adulterated and will not be adulterated, not repudiated by wise ascetics and brahmins. What five? Upholding the Five Precepts.” [“Streams” (A.VIII, 246)]

The Donee

There are some suttas that describe the person to whom alms should be given are: “Guests, travellers and the sick should be treated with hospitality and due consideration. During famines the needy should be liberally entertained. The virtuous should be first entertained with the first fruits of fresh crops.” [“The Benefit of Giving”, A.V, 35)]

There is also a recurrent phrase in the suttas describing those who are particularly in need of public generosity. They are “recluses, brahmans, destitute, wayfarers, wanderers and beggars. The recluses and brahmans are religious persons who do not earn wages. They give spiritual guidance to the laity and the laity is expected to support them. The poor need the help of the rich to survive and the rich become spiritually richer by helping the poor. At a time when transport facilities were meagre and amenities for travellers were not adequately organized, the public had to step in to help the wayfarer. Buddhism considers it a person’s moral obligation to give assistance to all these types of people.” [“Kutadanta Sutta” DN 5 (D.i, 137); “Payasi Sutta” DN 23 (D.ii, 354); “Cakkapatti Sihanada Sutta” D 26, (D.iii, 76)]

In the Anguttara Nikaya the Buddha describes, with sacrificial terminology, three types of fires that should be tended with care and honour. “There are these three fires that should be properly and happily maintained, having honoured, respected, esteemed, and venerated them. The three types of fire are of those worthy of gifts, the householder’s fire, and the fire of those worthy of offerings.” The Buddha explained that “one’s parents to be honoured and cared for, one’s wife and children, employees and dependents and the religious persons who have either attained the goal of arahantship or have embarked on a course of training for the elimination of negative mental traits. All these should be cared for and looked after as one would tend a sacrificial fire.” [“Sacrifice” (A.VII, 47(4)]

According to the Maha-Mangala Sutta, “offering hospitality to one’s relatives is one of the great auspicious deeds a layperson can perform.” (Sn.63).

In Kosalasymutta, King Pasenadi of Kosala once asked the Buddha to whom alms should be given. The Buddha replied that alms should be given to those by giving to whom one becomes happy. Then the king asked another question: To whom should alms be offered to obtain great fruit? The Buddha discriminated the two as different questions and replied that alms offered to the virtuous bear great fruit. He further clarified that offerings yield great fruit when made to virtuous recluses who have eliminated the five mental hindrances and cultivate moral habits, concentration, wisdom, emancipation and knowledge and vision of emancipation.

“With confident heart one should give to those of upright character. Give food and drink and things to eat, clothing to wear and beds and seats. So the wise man, faithful, learned, having have meal prepared, satisfies with food and drink, the mendicants who lives on alms, rejoicing, he distributes gifts and proclaims ‘Give, give.’ “ [“Archery” (S.I, 24(4)]

In the Sakkasamyutta, King Sakka asked the same question from the Buddha: Gifts given to whom bring the greatest result? “For those people who bestow alms, for the living beings in quest of merit, performing merit of the mundane types, where does a gift bear great fruit?” The Buddha replied, “That what is given to the Sangha bears great results.” Here the Buddha specifies that what he means by “Sangha” is the community of those upright noble individuals who have entered the path and who have established themselves in the fruit of sainthood, and who are endowed with morality, concentration and wisdom. The “Sangha” in the context of the Sutta means the four pairs of noble individuals or the eight particular individuals i.e., those who are on the path to stream-entry, once-returning, non-returning, and arahantship, and those who have obtained the fruits thereof.“The four practising the way and the four established in the fruit, is the Sangha of upright conduct and endowed with wisdom and virtue.” [“Bestowing Alms”, (S.I, 16(6))]

The Magha Sutta lll.5, gives a detailed account of the virtues of the arahant to show to whom alms should be offered by one desiring merit. (Sn.487 to 509)

The Brahmanasamyutta maintains that offerings bear greatest results when they are made to those who know their previous lives, who have seen heavens and hells, who have put an end to birth and who have realized ultimate knowledge. “One who has known the past abodes, who sees heaven and the plane of woe, who has reached the destruction of birth, a sage consummate in direct knowledge. Here one should give a proper gift, which bears great fruit.” [“Devahits”, (S.I, 13(3)]

Thus the Sangha comprising morally perfect, worthy personages as described in the sutta constitutes the field of merit. “When a bhikkhu possess ten qualities, he is worthy of gifts, hospitality, offerings, reverential salutation, an unsurpassed field of merit for the world. What are the ten? Here, a bhikkhu possesses the right view, intention, speech, action, livelihood, effort, mindfulness, concentration, knowledge and deliverance.” [“Bhaddali Sutta (MN 65)”, (M.i, 447)]

Just as seeds sown in fertile well-watered fields yields bountiful crops, alms given to the virtuous established on the Noble Eightfold Path yield great results. “When the field is excellent, and the sees sown is excellent, and there is an excellent supply of rain, the yield of grain is excellent. So too when one gives excellent food to shoes accomplished in virtuous behaviour, it arrives at several kinds of excellence, for what one has done is excellent.” [“Vaccha”, A.III, 57(7); “The Field” (A. VIII, 34(4)]

The Dhammapada maintains that fields have weeds as their blemish, lust, hatred, delusion and desire are the blemishes of people and therefore what is given to those who have eliminated those blemishes bears great fruit. “The results of generosity are measured more by the quality of the field of merit represented by the recipient than by the quantity and value of the gift given.” (Dhp. 356-59)

The Anguttara Nikaya records a fabulous alms-giving conducted by the Bodhisatta when he was born as a brahman named Velama. Lavish gifts of silver, gold, elephants, cows, carriages, etc., not to mention food, drink and clothing, were distributed among everybody who came forward to receive them. But this open-handed munificence was not very valuable as far as merit was concerned because there were no worthy recipients. It is said to be more meritorious to feed one person with right view, a stream-enterer, than to give great alms such as that given by Velama. “It is more meritorious to feed one once-returner than a hundred stream-enterers. Next in order come non-returners, arahants, Paccekabuddhas and Sammasambuddhas. Feeding the Buddha and the Sangha is more meritorious than feeding the Buddha alone. It is even more meritorious to construct a monastery for the general use of the Sangha of the four quarters of all times. Taking refuge in the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha is better still. Abiding by the Five Precepts is even more valuable. But better still is the cultivation of metta, loving-kindness, and best of all, the insight into impermanence, which leads to Nibbana.” [“Velama” (A.IX, 20 (11)]

The Motivation For Giving

“Mind is the forerunner of (all evil) states. Mind is chief, mind made are they. If one speaks or acts with wicked mind, because of that, suffering follows one, even as the wheel follows the hoof of the draught-ox. Mind is the forerunner of (all good) states. If one speaks or acts with pure mind, because of that, happiness follows one, even as one’s shadow that never leaves.” (Dhp. 1-2)

The Blessed One said in giving, the thought, intention and violation of the mind that count and not the quantity: “Not merely by efficiency of the gift does giving become especially productive of great fruit, but rather through the efficiency of the thought and efficiency of the field of those to whom the alms are given. Therefore even with so little as a handful of rice-bean or a piece of rag or a spread of grass or leaves or a gall-nut in decomposing (cattle-)urine bestowed with devout heart upon a person who is worthy of receiving a gift of devotion will be of great fruit, of great splendour and of great pervasiveness.” [“Pithavimana (The First Great Mansion)”, (Vim.l, 1)]

Thus, in Buddhist teaching, several motivations have been described that may exist in the mind of a donor when performing an act of giving: “One may give with annoyance in order to offend the recipient, One may give through fear, One may give to return a favour to the recipient, One may give hoping to receive a similar favour from the recipient; One may give because giving is good, One may give through altruistic motives, One may give to gain a good reputation, and One may give to adorn and beautify the mind.” [“Giving (1)”, (A. VIII, 31(1); “Giving (2)”, A. VIII, 32(2)]

Conclusion

Lord Buddha considered giving or generosity, as a fundamental and essential virtue in one’s spiritual development. Hence, whenever Buddha gave a discourse to those new to His teaching, a graduated approach was used that first discussed the importance of giving before discussing other aspects such as moral conduct, benefits gained in heaven, dangers of sensual pleasures, advantages of giving up and the deep aspects of the teaching such as the four Noble Truths.

Buddhism teaches a gradual process of emptying oneself. It starts with giving away one’s external possessions. When the generous dispositional trait sets in and is fortified by the deepening insight into the real nature of things, one grows disenchanted with sense pleasures. At this stage one gives up household life and seeks ordination. Next comes the emptying of sensory inputs by guarding the sense doors. Through meditation one empties oneself of deep-seated defilements and fills oneself with positive noble qualities. But this whole process of bailing out negativities starts with dana, the practice of giving.

Sadhu! Sadhu! Sadhu!

Contributor: Chin Kee Thou

Date: July 18th 2022

Contributor takes responsibility for any inadvertence, factual or otherwise